INTRODUCTION

The intersections between art and medicine have long captivated art institutions and artists, particularly with the rise of art-medicine and healing-centred practices since the 1970s (1). Both practices have long complex histories that can only be basically summarised here. Art, as a medium of creative expression, has historically sought to reflect the human experience, emotions, and social dynamics and operates at the intersection of aesthetics, culture, and human expression to create social forms of meaning-making. It is expressed using a wide range of media that is ever changing – and ideally is created for a diverse public to invite serious analysis and critique (2).

On the other hand, medicine is deeply rooted in practices that maintain physical and mental well-being, often referring to (medical) knowledge traditions and empirical data to better understand and address emergent health issues. On a more fundamental level, in traditional medicines – such as East Asian medicine practice, medicine is mainly concerned with how to live life well and to its fullest potential (3). These practices, although divergent in their methodologies and objectives, hold intrinsic value in our society.

By integrating technology and performance with the rich traditions of art and medicine, this integration not only involves technical production of spatial audio environments and clinical devices, but also uses the body as a technology (as a diagnostic tool) to critically reflect on the human technology relationship as well as to ethically consider the framework of technological production itself. By additionally using performance, which serves as an affordance for both the creation and enactment of social realities, both Qiscapes 氣穴音景 (2022–) and Pulse Project (2011–2017) use live performance as a dynamic medium capable of imagining and enacting complex social realities – as well as an affordance that communicates artistic research in an embodied, sensorial, and interactive manner.

Because there is an interrelationship of several knowledge practices within both Qisacpes and Pulse Project, these projects are most representative of transdisciplinary research where the aim of the research is to create a reorganisation and re-contextualisation of disciplinary knowledge into a multidimensional ‘complex’ of new knowledge (4). While transdisciplinary research can be approached through unifying objectives and outcomes across all disciplines to facilitate knowledge transfer across fields, which is especially true for science and technology communities whose methodologies often focus on reproducible results and impartiality (5) – such an approach presents problems for an arts context where research culture engages in producing subjective, practice-based, individualistic and unique forms of knowledge. To give an example of why impartial and transcendent or ‘objective’ approaches to transdisciplinary research may not be useful in the case of artistic research, Borgdorff writes that transdisciplinary research of disciplines such as: ‘performance practice… [and] specific movement repertoires, often cannot be, and does not wish to be, understood as research that transcends disciplines’ (6) since their interests lie in producing knowledge of ‘the unsolicited and the unexpected’ (7).

Thus the projects discussed in this article position themselves in alignment with Borgdorff’s (2012) and Leavy’s (2012) views of transdisciplinary knowledge production. That is to say, they are grounded within the ‘home discipline’ of artistic practice, which is utilised as a research methodology for examining and informing modern medical practices (such as rethinking diagnostic approaches and redesigning clinical tools) to produce new hybrid outcomes – and thereby widening this practice. At the same time, artistic research is used in this project to produce novel, indeterminate and unexpected understandings of the interplay between the body, technology and cultures. Furthermore, by using artistic practice as a transdisciplinary research methodology, these projects create new ways in which knowledge practices (disciplines) might be syncretically mobilised into new cartographies of knowledge – in direct contrast to the singular and linear approach to knowledge production utilised in traditional ‘mode 1’ (8).

Both the Qiscapes and Pulse Project performance research series address the set of problems that have emerged from real-world experience of practicing as an acupuncturist within a biomedical context – but from the perspective that adopts an artistic translation of this experience into a new social situation that is performed using Chinese medicine clinical methods and the creation of new sound interfaces. The interfaces developed for the performances not only strive to enhance the embodied well-being of participants by designing spatial sonic environments that emit frequencies considered beneficial to the body (9), but these performance interfaces also seek to facilitate the formation of communities interested in exploring diverse perceptions and conceptions surrounding the art-medicine-society relationship.

By inviting audiences to engage with the interpersonal and immersive spatial audio environments produced by Qiscapes and Pulse Project, individuals are encouraged to re-evaluate their perceptions of their own bodies and their relationships with the environment. These immersions then become a catalyst for allowing audiences to imagine the roles of artist, doctor, patient/participant and clinic from hybrid and diversified perspectives and to participate in multifaceted healing and well-being experiences that centre on inter-relational ‘being-with’ in the world.

The article commences by adopting a practice-based research perspective by introducing Qiscapes and Pulse Project performance research series, setting the stage for contextualising and analysing these projects through the lenses of related key discourses and peer projects. By embracing the concept of the interface, the subsequent sections not only reconfigure the relationship between art, medicine, and society but they also embark on an exploration of alternative forms of care and interconnectedness through the material construction of performance interfaces.

RESONANT EMBODIMENT: CHINESE MEDICINE PERFORMANCE INTERFACES

This section introduces the Qiscapes and Pulse Project performances, laying the groundwork for their contextualisation, comprehensive analysis, and scholarly discourse. As these projects intersect with a wide range of disciplinary and cultural domains, this introduction forms a critical focal point for our further exploration of these domains throughout this article.

QISCAPES (2022 -)

The images below document a series of publicly engaged performances that sonify and evidence ‘qi’氣 – a phenomenon/ substance generally thought not to exist. For these performances, I have created the ‘acupunctosonoscope’ – a biosonic instrument prototype that combines an acupuncture clinic device with Max/MSP, a microcontroller and a soundcard to amplify the live flow of bioelectric signals (qi) (10) moving through specific acupuncture points within participants’ bodies (flowing differently within each individual). In this way, the instrument sonically maps and evidences the body in accordance with traditional East Asian medical anatomy texts and immerses audience participants within spatially dynamic sound fields created by the points and meridians hidden within their own bodies in real time. In this way, Qiscapes (11) performances develop a sonic technology that ‘cares’ for the social body – as the performances produce bespoke therapeutic soundscapes that use frequencies considered beneficial for specific organs according to traditional Chinese medical texts (12).

Figure 1. Qiscapes Performance, Points Art Center, Jinxi, China, 2022. Michelle Lewis-King. Photo: Courtesy of Points Art Center.

Figure 2: Detail of the Acupunctosonoscope, Michelle Lewis-King, 2019.

Figure 3: Performance detail, Michelle Lewis-King, 2022. Photo: Courtesy of Points Art Center.

The video below shows live sonification of acupuncture point location and demonstrates the accuracy of the acupunctosonoscope instrument. Performances can be a surprising experience for audiences as many believe these points do not exist. This was especially in China – as everyone learns basic Chinese medicine theory from studying classical literature for high-school exams – nonetheless – many remain skeptical about the existence of acupuncture points and are shocked and sometimes delighted to discover the possibility that they might actually exist.

Video 1: Qiscapes Acupunctosonoscope prototype, Michelle Lewis-King, 2022.

PULSE PROJECT (2011-2017)

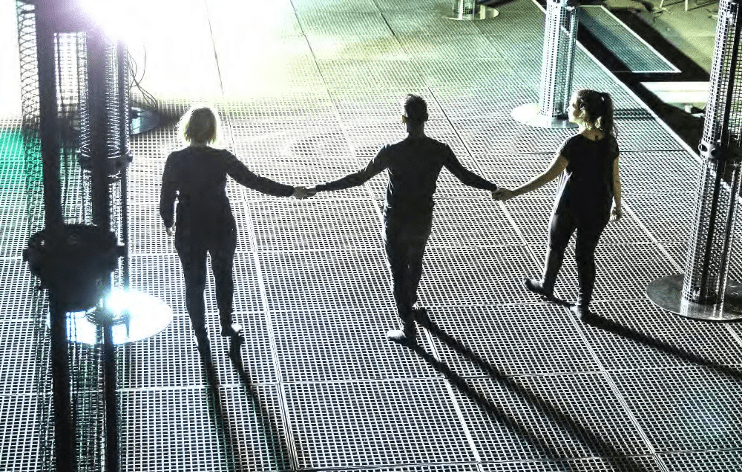

Figure 4: Pulse Project by Michelle Lewis-King; performance at the V&A, Victoria and Albert Museum, 2013. Photo: Nick Fudge.

For this project, Chinese pulse diagnosis was adapted as a performance tool. This followed on from many years of reading pulse waveforms emerging from peoples’ bodies as the main diagnostic tool for determining the condition of peoples’ health (from the perspective of the organ-network system of Chinese medicine) within my clinic. From this experience, I came to realise that human touch is itself a technology. It can be used both as a diagnostic instrument yielding medically relevant information, as well as a creative tool capable of developing musical-artistic interpretations of the body. In turn, the soundscapes produced from these readings opened up new resonant spaces that interconnect art and medicine knowledge practices and, in this way, create new forms of medical meaning (healing transformation).

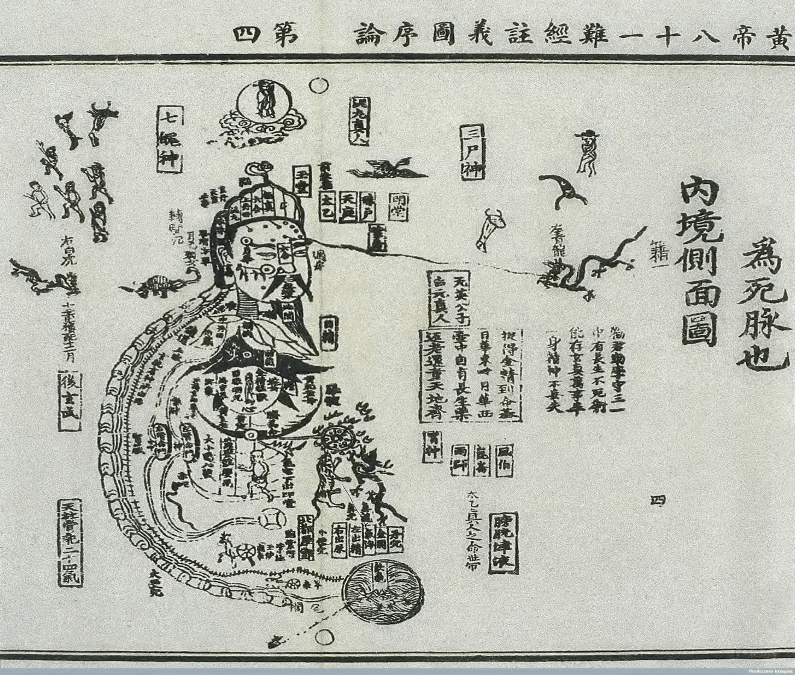

In Chinese pulse diagnosis (13), there are 28 ‘classic pulse-wave images’ (refer to Fig. 5 as an example of just a single ‘pulse image’, out of many) from which to identify physiological patterns occurring within the meridians and organs of the body (14). During Pulse Project performances, I analysed each person’s pulse as a set of unique rhythmic sound waves that were then transposed into bespoke musical notations (this could be hand-drawn or painted musical scores – see Fig. 6 as an example).

Figure 5: Yin Weimai Pulse Image, woodcut, circa 180-270 CE. Attributed to Wang Shuhe and edited and revised by Shen Jifen, 1368-1644. Source: Wellcome Trust Library, Creative Commons.

Figure 6: Cambridge Notation 1, ink painting on acetate, Michelle Lewis-King, 2014. Photo: Léna Lewis-King.

These notations were then used to create immersive soundscapes so that the unique rhythms and frequencies of each person’s organ-networks could be given exterior dynamic form (see Fig. 8 which shows the immersive sound environment of Pulse Project). At the same time, this work also promoted well-being – as the frequencies within the soundscapes were tuned to pitches that have been identified as beneficial to human organs (15). Instead of interpreting the Western notion of the circulatory system, the project draws upon specific early Chinese medical philosophies and music theories in order to represent a person as a living cosmos – as a relational body-consciousness pulsating with matter and energy. By working with Chinese pulse diagnosis as a method of medical and artistic analysis for bodily rhythms and producing notations and soundscapes as sonic ‘prescriptions’, Pulse Project questioned the fundamental metaphysics of medicine and technology as they have been shaped by Western thought.

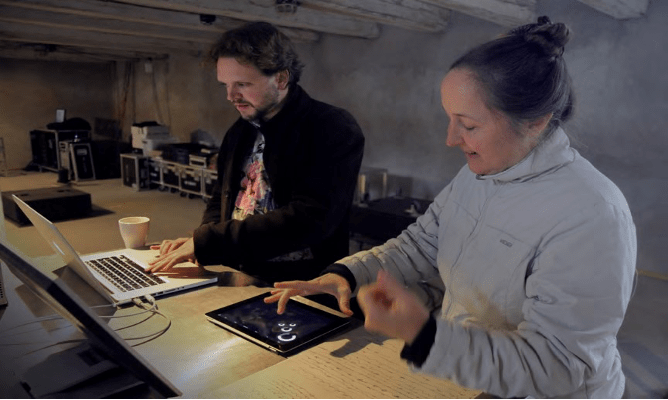

The images and videos below demonstrate examples of my collaboration with 4DSOUND on a commission by TodaysArt to develop a live spatial sound performances of Pulse Project for TodaysArtNL 2015 in Den Haag. This interface allowed me to perform my interpretation of participants’ pulses to a broader audience (16). Utilising a touchscreen controller, such as an iPad, and Ableton Live software that connected the Pulse Project interface to the 4DSOUND system, I not only composed and broadcast my interpretations of participants’ pulse readings within a live sonic environment but also transformed participants’ infrasonic body dynamics into uniquely sculpted sonic architectures in alignment with the metaphysical principles of Chinese medicine.

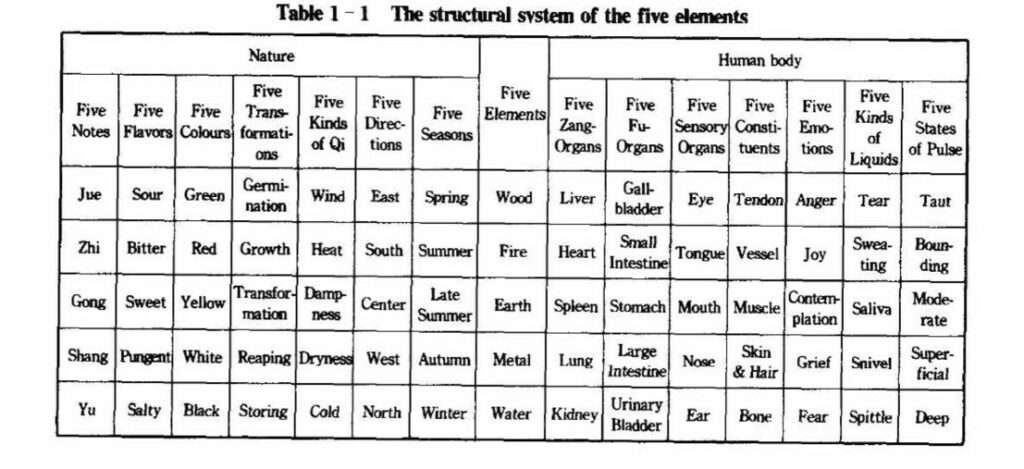

Pulse Project’sand 4DSOUND’s‘Five Element Interface’ is a graphical user interface (GUI) (17) that contains five pages representative of the Five Elements. On each of the GUI pages are a set of four main controls – two controls for each organ-network, making twenty controls overall (see Fig. 7 showing Ooman and I working on one of the Five Element pages). Each control on the iPad GUI enabled me to also work with spatial sound via the Five Element Interface’s connection with the 4D.Animator – 4DSOUND’s software tool that made it possible to sculpt the unique dynamics of each participant’s zàng-fǔ (according to their pulse notation) into real-time spatial sound within the architecture of the Electriciteitsfabriek and the 4DSOUND system (this is demonstrated further in videos 2–3 below).

Figure 7: Pulse Project by Michelle Lewis-King at 4DSOUND. Development of the Five Element Interface with director Paul Oomen, 2015. Photo: Courtesy of 4DSOUND.

Figure 8: Pulse Sound Sculpture 14 by Michelle Lewis-King at TodaysArt NL, 2015. Circadian: 4DSOUND. Photo: Florence To.

Video 2 below demonstrates personal interaction between the performer (myself) and the film-maker participant and takes us through the process of pulse-analysis, notation creation, and using the Five-Element Interface within the 4DSOUND system to produce the rhythmic internal sounds of the organs according to each element in Chinese medicine.

Video 2: Pulse Project by Michelle Lewis-King at 4DSOUND, Budapest, 2017. This video is an excerpt from a documentary of the residency and performance for Reflections from the Inner Mirror at 4DSOUND by Daniela del Pomar and Paul Holdsworth of Quiet City Films, Berlin. Chinese Subtitles by Yuzhen Tang.

Video 3 was produced by Paul Oomen for the Red Bull Music Academy (18) to demonstrate the way the 4D.Animator sculpts the shape, expression and trajectory of each sound ‘element’ as it moves across the 4DSOUND system in accordance with the principles of Chinese medicine theory.

Video 3: Pulse Project at 4DSOUND – Five Element Interface. Excerpt of the 4D.animator graphic interface that demonstrates how the sounds of each ‘element’ such as wood, water, metal, etc., move within the 4DSOUND 62 speaker system of to create spatial sounds of the body according to Chinese medical theory. Video courtesy of 4DSOUND and Red Bull Music Academy.

The audio tracks below demonstrate multi-channel soundscapes composed from reading individual’s pulses using SuperCollider, which formed part of my doctoral thesis project ‘Pulse Project’ (2011-17) at Cambridge School of Art. Each composition is tuned to a specific frequency to create healing soundscape ‘prescriptions’. This is because the tones selected are thought to be beneficial for specific organ-networks according to five-phase/wŭxíng (五行) theory of Chinese medicine. For example, the ‘Earth’ pitch at 261.6 Hz (in Audio 1, below) is said to improve stomach and spleen system functioning according to the Yellow Emperor’s Internal Classic (Huangdi Neijing -黄帝内经) and recent clinical trials (19). This example represents just one of the five music tones, each which is associated with a season, sound and organ network. They are utilised in the Chinese Medicine clinic to establish resonant connections between the human body (phenomena) and the seasonal movements of the dao (noumena). The audio samples bellow were part of my doctoral thesis project ‘Pulse Project’ at Cambridge School of Art (2011-17).

Audio 1: Pulse-Landscape – Central Saint Martins 1. 宫 (Earth) 2013. Soundscape created from pulse reading using SuperCollider. This ‘Earth’ pitched soundscape demonstrates adopting the five-phase theory of Chinese medicine (五行) into soundscape composition. It is part of Michelle Lewis-King’s doctoral thesis at Cambridge School of Art.

Audio 2: Pulse-Landscape – Hastings 商 Metal) 2015. Soundscape created from pulse reading using SuperCollider. This ‘Metal’ pitched soundscape demonstrates adopting the five-phase theory of Chinese medicine (五行) into soundscape composition. It is part of Michelle Lewis-King’s doctoral thesis at Cambridge School of Art.

Audio 3: Pulse-Landscape – Anatomy Museum London 5 徵羽 (Fire-Water) 2015. Soundscape created from pulse reading using SuperCollider. This ‘Fire-Water’ pitched soundscape demonstrates adopting the five-phase theory of Chinese medicine (五行) into soundscape composition. It is part of Michelle Lewis-King’s doctoral thesis at Cambridge School of Art.

Audio 4: Pulse-Landscape – Copenhagen 2 角 (Wood) 2015. Soundscape created from pulse reading using SuperCollider. This ‘Wood’ pitched soundscape demonstrates adopting the five-phase theory of Chinese medicine (五行) into soundscape composition. It is part of Michelle Lewis-King’s doctoral thesis at Cambridge School of Art.

Instead of interpreting the Western notion of the circulatory system, this work draws upon specific early Chinese medical philosophies and music theories in order to represent a person as a living cosmos – as a relational body-consciousness pulsating with matter and energy. By working with Chinese pulse diagnosis as a method of medical and artistic analysis for bodily rhythms and producing notations and soundscapes as sonic ‘prescriptions’, Pulse Project questions the fundamental metaphysics of medicine and technology as they have been shaped by Western thought.

PARTICIPANT RECRUITMENT

For both projects, the research focus does not revolve around achieving ‘objectivity’, which is the conventional approach in medical research trials. Instead, I sought to challenge this paradigm by adopting a perspective that views clinical practice as the construction of ‘situated’ and relational knowledge practices (20). My own clinical experiences revealed that clients/patients choose to pursue treatments for various reasons, namely: personal interest in the therapy, knowledge about Chinese medicine, and a desire for a meaningful therapeutic relationship to address their concerns. These insights stem from numerous conversations with clients and patients regarding their motivations for seeking treatment and reflections on the effectiveness of the treatments.

Consequently, the framework for participant recruitment in both Qiscapes and Pulse Project was often designed in collaboration with event organisers. Posters and information brochures outlining programme content and schedules were the main access to information on the performance research. The posters, brochures and schedules were distributed at numerous conferences, digital art festivals, museums, galleries, and art-science events where Qiscapes and Pulse Project were performed across the UK, Europe, and China.

PERFORMANCE SET-UP

The performances are intentionally minimalist, typically featuring only a table, two chairs, ink, paper, and a computer (plus a sonic point-location device in the case of Qiscapes). During the initial phases of Pulse Project, which was initially part of a doctoral research project, participants were provided with comprehensive ‘participant information sheets’. These sheets not only outlined the performance procedure but also included a consent form that participants were required to sign before taking part. Typically, these events began with a research presentation, followed by performances with scheduled slots for participants to sign up. In the case of Qiscapes, participation tends to be voluntary, as the instrument’s operation is entirely safe. The sounds produced by the points via the acupunctosonoscope pique audience curiosity about what their own acupuncture points might sound like – which also motivates audiences to participate.

AIM OF PERFORMANCES

In merging art, technics, and Chinese medicine, my aim is to reframe and redefine technoscientific activity from a fresh perspective. These performances demonstrate how the intricate relationship between the body, environment and cosmos can generate profound resonant meaning. Rather than relying on modern scientific instrumentation, which often detaches nature from cultural knowledge production (21), my work focuses on harnessing the inherent intelligence of the sentient body in relation to technics, within the frame of the clinical encounter. In using sound as the main performance medium, each soundscape is designed to both respond to the rhythms and frequencies of audience participants’ bodies and to enable meaningful health-promoting interactivity between the infrasonic interior of the body and exterior digital assemblages of rhythmic sound. This takes place though embodied experience itself – as significant physical understandings, e.g., art-medicine meaning-making, can only be realised via the body’s sensible interaction within sonic fields (22).

THE PERFORMANCE OF CHINESE MEDICINE AND CLINICAL PRACTICE AS COSMOTECHNICS

This section begins by providing context for Qiscapes and Pulse Project through an exploration of personal clinical experiences that influenced their research directions. It also offers an introduction to the fundamental principles of Chinese medicine before moving on to a discussion of how interdisciplinary practices spanning art, Chinese medicine and technology present a novel cosmotechnical approach to interface production.

ART IN THE CHINESE MEDICINE CLINIC

As an artist who practices medicine, my keen interest lies in the harmonious synergy of these distinct disciplines, where each informs the other to enrich overall well-being. This broader perspective encompasses not only physical health but also mental and spiritual wellness. However, the primary challenge I faced in my clinical practice was the stark contrast between the experiential, interactive, and artistic dimensions of Chinese medicine practice (which I discovered to be immensely influential in nurturing both somatic and spiritual well-being), and the definition of ‘valid’ medical practice, often centred around biomedical models rooted in mechanistic thinking.

This constant requirement to validate the efficacy of Chinese medicine within the framework of biomedical practice and research (and the deeper political reasons why this is not as straightforward as it appears) (23) serves as the foundation for the development of research questions and concerns related to my artistic practice. It also prompted me to explore whether artistic research methods, with their alternative perspective on diagnostic processes, could introduce a new dynamic into the creation of medical knowledge. My aim then developed to encompass the use of artistic research as a catalyst for the emergence of novel forms of (medical) healing knowledge (24).

In this way, the primary concerns of my transdisciplinary work, that of using artistic research to query the body’s relationship to technology, science and society arose from my experience of the hegemony of the clinic (25). Because Chinese medicine does not easily conform to the design of evidence-based medicine (EBM) and biomedical practice models, consequently, its significances are often positioned as marginal to the significances of biomedical knowledge. Furthermore, Chinese medicine’s difficulties with ‘compliance’ in terms of conforming to EBM protocol structures often results in persistent claims of doubt as to its clinical effectiveness by medical professionals who adhere to the sentiment that the biomedical paradigm represents the only ‘one, reality, one truth’ (26). The result of this situation is that the sustainability of Chinese medicine practice remains uncertain (27).

For this reason, both Qiscapes and Pulse Project strive to reimagine prevailing art-medicine paradigms that mostly rely on biomedical constructions of medical knowledge. Instead, these works endeavour to reimagine and diversify what medicine and the body are or could be by using the Chinese medical encounter within a digital performance context to challenge conventional perceptions, thereby opening up novel dimensions for comprehending the intricate relationality between the body, environment, and cosmos.

INTRODUCTION TO CHINESE MEDICINE PRINCIPLES AND THE ‘BODY ECOLOGIC’

To facilitate a deeper understanding of these projects, it becomes essential to provide a foundational explanation of Chinese medicine theory and practice within this section to provide an important context for the ensuing discussions. Chinese medical systems – which comprise both clinical and scholarly discourses in philosophy, theory, analysis, diagnosis, and treatment can be traced back to at least 221 BCE (28). For this reason, giving a concise account of its richly complex principles and practices can only be described superficially here (29).

Chinese medicine draws on over a thousand years of artistic, scientific and technological innovations – and each innovation in itself contains untold histories, intangible cultural heritages and cosmological heaven-human-earth/天人地 integrating practices. (30). From this rich tapestry, the Chinese medicine encounter emerges as a multidimensional space where practitioners adopt a wide range of differing (often contradictory) strategies and interventions for working with the living ecosystems of the body-lifeworld inter-relationship. Within the theatrical framework of the Chinese medicine clinic, it is precisely its transdisciplinary, intercultural and diachronic (premodern and contemporary) practices that mark it out as a unique area of study.

To establish a foundational framework for the body within the context of Chinese medicine, it is important to recognise its historical development is intricately intertwined with the methods and concepts formed by both political and agricultural practices that emerged within early Chinese societies (31). In The Transmission of Chinese Medicine (1999), Elisabeth Hsu – Oxford Professor of Anthropology highlights the early Chinese perception of the body as an interconnected organism with ecological and political implications, as evident in the following excerpt:

“The notion of the ‘body ecologic’ highlights the idea of mutual resonance between macrocosm and microcosm and the continuities between the inside and the outside of the physical body. The ‘shared substrate’, qi, that permeates the universe constantly transforms itself: qi is not only in constant flow, but also in constant flux (in the sense that it is subject to constant transformation). This conception of the body as part of its environment is characteristic of Chinese medicine. Notably, the ‘body ecologic’ is, like the body politic, intricately intertwined with its environment, so body and environment cannot be dealt with as separate entities. This contrasts with the [Western] notion of the individual and the social body, which refer to a clearly bounded, ‘classical’ body.” (32)

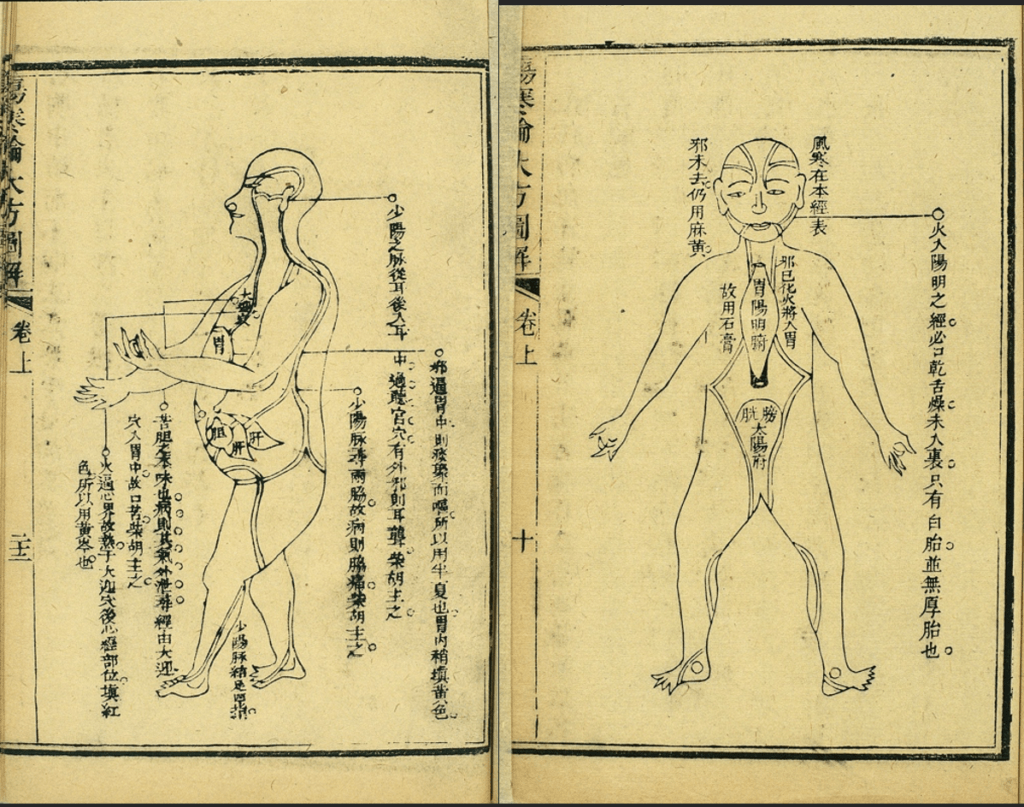

In line with this perspective of viewing the body as a political entity, which simultaneously maintains coherence and embraces the transformative processes of life, Chinese medicine conceptualises the body as an interconnected organism that is not a discreet from – but actively interacts with natural, technical, and sociocultural structures. These structures themselves are in a constant state of flux. Another key aspect of the Chinese medical understanding is of the body as a microcosm of the natural world, a coherence that comprises various interrelated substances and essences, while at the same time, these substances are themselves also inter-relating with the lifeworld (see Fig. 9 below).

Moreover, the interactive processing of internal (micro) and external (macro) coherences and substances within and around the body-lifeworld complex are shaped and mediated by specific alchemical properties and processes that the early Chinese defined as yīnyáng 阴阳 and wŭxíng 五行. In this cosmology, all matter and energy are processual, are moving and interacting, and as such, they are absent of the Western conception of fixed or discreet biological objects and taxonomies.

The concept of yīnyáng wŭxíng processes, characterised by their animating presence, permeates all forms of existence, including non-human life. In early China, this inter-relational perspective was revered as a fundamental aspect of the universe’s cosmological order. It aligns closely with the essence of life itself, as its intricate and unfolding facets demand an approach to medical study that can grapple with the continuous interaction, mutual restraint, and interdependence of matter and energy. These principles, embodied in the concept of primordial ‘yīn and yáng substances’, encapsulate a non-dual and relational methodology for studying the dynamics of life – providing a contrasting perspective to ‘life sciences’ studies of the biological.

This approach acknowledges the inherent opposition yet perpetual dynamism of these principles, offering a profound and entangled view of life’s unfolding through time – one that is vibrant and dynamic and not fixed. In fact, if we separate y yīn from yáng or disrupt their interaction, the life processes they refer to eventually stagnate, leading to disease and eventual demise (33). Thus, in Chinese medicine, the body is conceived as a multi-dimensional entity shaped and influenced by the interplay of interior and exterior yīnyáng wŭxíng processes.

Figure 9: Neijing Tu (1436-1443), Li Jiong, woodcut. Wellcome Trust Library, Creative Commons.

The most important bodily substances of the Chinese medical cannon are termed: jīng, qì, shén, and for this reason are called the ‘three treasures’ of existence.

Translated loosely, these terms refer to the following:

jīng 精 refers to the ‘essence’ of humans and nonhumans alike. It possesses both yīn and yáng aspects. The yin aspect represents inherited essence of a specific quantity that is metabolised or used-up over a life-time (similar to DNA and the study of epigenetics in biomedicine). The yáng aspect is acquired throughout life and involves maintaining the original essence through nutrition, exercise, meditation, and so on. A person dies when the jīng is consumed (34).

qì氣 represents the primordial cosmic substrate that is active both inside and outside the body, and leads dynamic action and processing (35).

shén 神 is housed in the heart and embodies the spiritual essence that connects the human (animal) mind with cosmic consciousness and represents the most refined and clearest aspect of bodily qì (36).

Then the body is further categorized into other ‘vital substances’: organs (zàng-fǔ 脏腑), energetic conduits (jīng-luò 经络), blood (xuè 血) and body fluids (jīnyè津液).

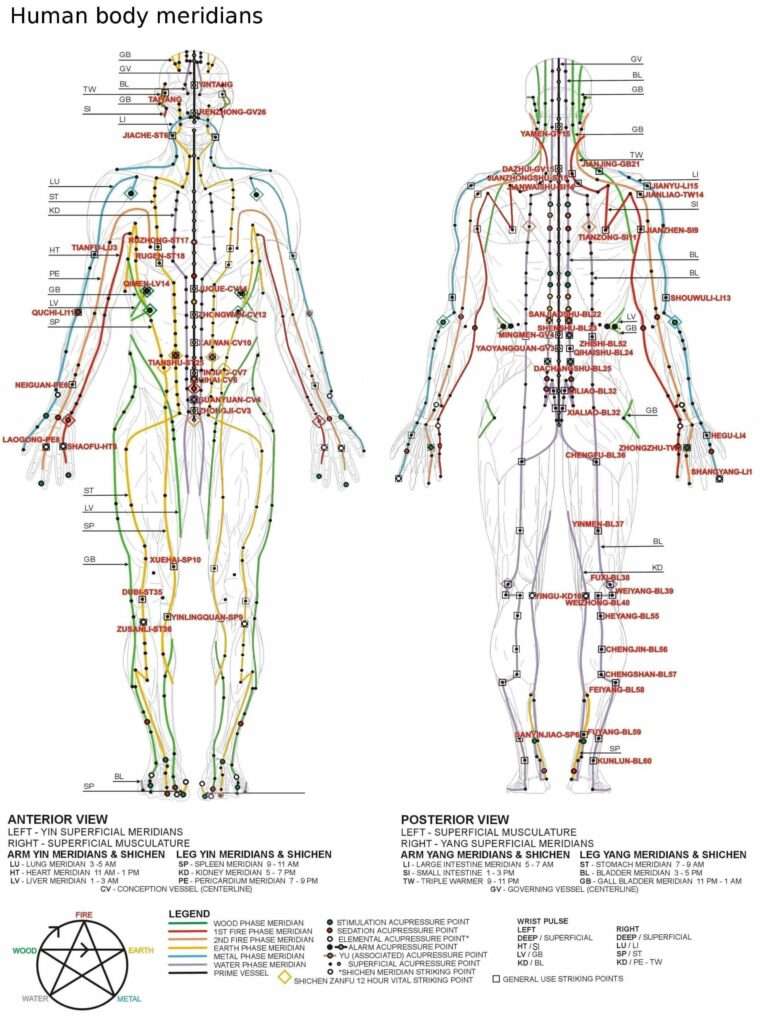

To go a little deeper into the conception of the Chinese medical body, we start with the organs – which are organised into five yīn (solid) organs, known as the zàng 脏 – which contain and store vital substances. This includes: the heart (including the ‘pericardium’), spleen, lungs, kidneys, and liver. Additionally, there are six yáng (hollow) organs, known as fǔ腑 – which transform substances into metabolic energy or bodily ‘qì’. This includes: the small intestine, large intestine, gall bladder, urinary bladder, stomach, and triple heater (sān jiǎo三焦). There are also the extraordinary fǔ organs, that include ‘the brain, the marrow, the bones, the vessels, the gallbladder, and the uterus’ (37). Each of these organs is associated with energy reservoirs or networks referred to as jīng-luò 经络 that run between the internal organs and the external periphery of the body (38). This relationship can be viewed in the image below (Fig. 10), which illustrates how herbal medicine is interacting with the stomach, gall bladder, and bladder organs and meridians. Fig. 11 below demonstrates a more modern interpretation of the channels/ jīng-luò themselves.

Figure 10: Left – “Theory of diseases treated with blupeurum decoction”, woodcut, Chinese, unknown author, 1833. Right image – “Theory of Diseases treated with da qinglong decoction” woodcut, Chinese, unknown author, 1833. Wellcome Collection, Public Domain.

Figure 11: Human body meridians (2010)(39), digital image. By KVDP, Wikimedia Commons. Creative Commons Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

In addition to the dynamic interplay of yīnyáng, the concept of wŭxíng encompasses the cosmological processes understood as five ‘movements’ or phases and qualities (instead of ‘elements’) as they are not fixed but are inter-relationally animate. These movements can be observed as dynamic changes that take place within the movement of seasons– as well as within natural phenomena as they interact in relation to the changes of climate, and so on. Early Chinese divided these changes into five main phases. This includes:

- ‘Wood’, which is characterised by growth and movement and corresponds with the spring.

- ‘Fire’, characterised by with heat and upward expansion and corresponds with the summer.

- ‘Earth’, which embodies the abundant and nurturing qualities of the soil and corresponds to late summer.

- ‘Metal’, a movement which reflects the contracting and precise nature of the autumn harvest.

- ‘Water’, which is characterised by the cooling, sinking, and storing capacities of fluids in winter.

These elemental phases are not confined solely to external manifestations through seasonal cycles – but are equally operational within the body – governing its functional processes and essential substances. Moreover, these internal and external phases share specific, interconnected relationships with each other. For a visual representation of these inter-relationships, please consult the image provided below (40).

Figure 12: The structural system of the five elements (2016), digital image. From TCM/ Wiki, Creative Commons ShareAlike 4.0.

Overall, there are twelve organ-networks (41), which are closely interlinked with the previously mentioned wŭxíng/five elemental phase processes, as depicted in Fig. 9-12 above (42). For example, the stomach and spleen organ-networks’ metabolic processes of ‘rotting and ripening’ food to transform it into clear energy and turbid waste respectively are reflective of ‘earth’ qualities and processes. Similarly, the contracting and expanding functions of the lung and large intestine of during respiration and peristalsis in digestion as well as filtration of air and ingested food for valuable substances reflects the qualities and processes of ‘metal’. As the kidney and urinary bladder are responsible for the metabolism and homeostasis of fluids and reproductive functions – they are reflective of the fundamental and ‘source’ qualities of water. The liver and gall bladder govern the systemic metabolic interactions of the organs (akin to the role of hormonal/endocrine systems in biomedicine) that reflect a similar complexity and dynamism of plant systems and are considered ‘wood’ for this reason. The the heart and small intestine are connected to the mind and the shén 神 and govern the circulation of blood and qì in the vessels and channels/networks. Additionally, the ‘triple heater’ and pericardium both protect the body from exterior pathogenic invasion and facilitate energetic and fluid metabolism across the lower, middle and upper parts of the body. They are associated with ‘Ministerial’ fire processes – which uniquely possess both water and fire attributes (43).

In the entangled set of relationships described above, the organ-networks both constitute a part of and are significantly influenced by the dynamic interplay between exterior and interior yīn-yáng wŭxíng processes. This perspective dismisses the notion of separating the body from mind (a hallmark of Cartesian-influenced Western medicine and philosophy). Instead, it perceives them as interconnected through the shén-spirit, flesh, viscera, and organ-networks. Consequently, it envisions the body and mind as an integrated system, forming an ecological entity in perpetual internal transformation, constantly interacting with the ever-changing external environment. In this way, the ecological body of the organ-networks (zàng-fǔo jīng-luò) serve as an interface that bridges the realms of the body, environment, and cosmic forces.

THE COSMOTECHNICS OF THE CHINESE MEDICINE CLINIC

At the heart of the performances, the clinical encounter itself is used as a primary investigative tool for unlocking a set of socio-technological inter-relationships between the human body and the phenomenal world. To understand how the frame of the clinic itself creates cosmological knowledge that brings together individuals, tools, and the exploration of the phenomenal world, this section opens with a discussion of Heidegger’s ‘gestell’ – or the act of ‘enframing’ as the essence of the technological (44).

In Heidegger’s ‘The Question Concerning Technology’ (1977), he critically engages with the modern development of technology, uncovering its inherent extractive approach to understanding nature. According to Heidegger, our (human) drive for control steers us towards dominating nature by using instruments to enframe it. However, he does highlight a grave concern — which is the lack of criticism towards how this technological enframing exploits and consumes the very essence of nature it aims to understand (45). As a consequence, nature, and eventually humanity, become reduced to mere resources ready to be utilized as ‘standing-reserve’ (46). Heidegger’s insights compel us to contemplate the intricate relationship between technology, knowledge, and the natural world, raising essential questions about our role as stewards or carers of the planet.

Consequently, Heidegger suggests that the sustained (technoscientific) focus on enframing forecloses upon what could be a more liberating use of technology, to use it as a tool for generating poetic instead of purely technical knowledge of the natural world. He thus urges us to abandon the use of technics to engineer the truth as an a-priori – and instead to embrace a poetic orientation towards technical production in a way that seeks to understand nature on its own terms (47).

Such an approach has its roots in an orientation towards care for and of the lifeworld, and as such, it has the potential to repair damage done to the environment, peoples, etc., and to move us away from an exploitative stance towards nature and technology. Instead, we can use technics to foster a harmonious construction of ‘truth’ (culture) – as a production that considers or participates in its entanglement with the nature we seek to understand (48). Heidegger’s call for a more ethical technics could then be reframed somewhere within the scope of what feminist scholar Donna Haraway refers to as ‘nature-cultures’ (49) – or what comes to mind when creating technologies – a creative process that is intimately interconnected with the unfolding of fractal inter-connected worlds that are inseparable and ever-mysterious.

Yuk Hui, philosopher of technology, expands upon this in his work The Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics (2016), where he identifies that Heidegger’s question about technology is even more pressing in the age of the Anthropocene (50). Hui’s criticism focuses on global technical hegemony and proposes the development of a ‘cosmotechnics’ that is diverse and locally situated. Throughout his many talks and articles, Hui makes an impassioned argument for resisting the inherent fascist drives towards a technological ‘singularity’ – and calls for the creation of technics that is diverse and creates interconnections between communities in new ways. One way of accomplishing this, Hui suggests, is through reexamination of traditional Chinese thought. His goal is to restore a missing aspect from technoscientific production – which is the moral (ethical) relationship between tool production (qi 器) and the environmental and cosmic context in which tools are used (dao 道).

Expanding on Heidegger’s call for ethical consideration in creation of technics within the lifeworld, Hui introduces cosmotechnics as a means to reverse the extractive relationship between technological production and natural resources driven by modernity and capitalism (51). In doing so, cosmotechnics offers a curative, ethical, and diversified approach to addressing humanist concerns amidst the challenges of the Anthropocene era.

Cosmotechnics is described by Hui as “the unification of the cosmos and the moral through technical activities, whether craft-making or art-making. There hasn’t been one or two technics, but many cosmotechnics.” (52) Hui expands on this by discussing the historical development of technology in ancient China and highlighting its ability to maintain a harmonious figure-ground relationship (53) in the production of knowledge. He argues that this approach to technology becomes a crucial means of addressing and resolving the dichotomy between nature and culture perpetuated by modernity (54).

Through exploring the concept of Ganying (感应) or mutual resonance, Hui discusses the ways in which feeling, touch or sensibility were used in early China to create interconnections and metaphysical ecologies between emergent forms, appearances and patterns in the world as integral to the process of producing technics. Hui refers to this process of creating technological objects (qi器) as something that occurred through aligning the mind/consciousness with ritual behaviour and the gestalt unfolding of the phenomenal world and noumenal universe (dao 道). It is this complex interactive and cosmotechnical creation of technology that Hui terms as ‘cosmotechnics’ (55). I identify Hui’s cosmotechnical interconnection between the human body-mind, place-ritual, and time-space as an ideal framework for shaping the understanding of the interfaces developed in Qiscapes and Pulse Project performances – which use technics to interconnect the ecological body of Chinese medicine, artistic and medical practices with immersive experiences that produce mutual resonances between bodies and the environment, to create reparation and healing.

By adopting a cosmotechnical perspective, I explore the transformative potential of integrating the creation of nonmodern and non-Western technologies in tandem with the unfolding of the natural world, thus putting into practices a more synergetic relationship between human beings, technological development and the environment. This approach challenges conventional notions of technology as something separate to or in control of nature. It encourages a deep integration of body, mind, and nature-cultures in the pursuit of knowledge production and creative expression.

ART-MEDICINE PROJECTS

In this section we will explore artistic research projects and discourses most relevant to Qiscapes and Pulse Project, via exploration of the transdisciplinary genres of biomusic, spatial sound and art-medicine studies, as these genres closely correspond to the specific intersections that Qiscapes and Pulse Project’s performance research encompasses. To the best of my knowledge, Qiscapes/Pulse Project are unique as there are currently no other projects that integrate these specific areas of practice together in a comparable manner.

ART-BIOMEDICINE PROJECTS

When I first initiated my art-medicine research in 2010, this interdisciplinary field was still in early development. Prior to this period, the majority of art-medicine projects were a result of the Wellcome Trust’s ‘Sciart’ program, which operated from 1996 to 2006. During this initiative, funding supported collaborations between artists and scientists, resulting in 118 projects dedicated to the exploration of biomedical science. The projects were funded to:

- Stimulate interest and excitement in biomedicine in adults.

- Foster interdisciplinary and collaborative creative practice in the arts and sciences.

- Create “a critical mass of artists looking at biomedical science and build capacity in this field” (56).

This created an emerging field of practice in Britain that began to become influential worldwide through wide media coverage (57) and it was seen to have greatly strengthened research and development between the arts and sciences. However, due to the Wellcome Trust’s focus on knowledge transfer (which resulted in somewhat conservative exploration of topics and outcomes aimed only in relation to the scientific agenda), as well as the restrictions in the funding for each project towards furthering the causes of biomedical aims and objectives only – these aspects were seen to set up a hierarchy between art and science which heavily influenced the types of work undertaken in this genre, which often was not motivated by artistic objectives (58).

Throughout my doctoral studies (59), spanning from 2011 to 2017, my artistic research sought to offer a perspective that set itself apart from other art-medicine projects characterised by their predominant reliance on biomedicine as the primary investigative approach. My focus was on reevaluating the clinical encounter from critical and innovative standpoints. I focused on the idea of shifting the emphasis from always validating Chinese medicine within a biomedical framework towards investigating how Chinese medicine could provide fresh insights into medical and aesthetic concepts related to the body, health and well-being. In doing so, my research aimed to reveal some of the limitations inherent in conventional biomedical thinking. It was this perspective that laid the foundation for the development of Pulse Project and Qiscapes.

Along similar lines, artist-researcher Kaisu Koski (60) has also studied the doctor-patient relationship and the medical body as part of her doctoral and post-doctoral research. Within this art-medicine context, Koski uses her artistic research as a social activist practice that seeks to contribute to the field of bioethics. To this end, Koski writes:

“In my postdoctoral research project art is set in an instrumental position (…) aiming to unveil the medical body conception. In this project the artistic research methods and expression create a space in which imaginative scenarios and personal viewpoints are not only allowed but also necessary, and the views on what health and healthcare means can be analysed, criticized and fanaticized… the findings and reflections are both embedded in the same product, whether it is a publication on paper, screen or space.” (61)

Here Koski argues for a form of artistic research that can inform medical practice and widen the biomedical notion of the body – an aim that is also likewise central to my project. Additionally, Koski aligns her methodological approach more with social science research than studio art research, and argues that practicing artistic research in settings outside the context of art institutions provokes social change by simultaneously rethinking the function of artistic practice within society and also using artistic research to ethically rethink medical practice and contribute towards biomedical ethics (62). Qiscapes and Pulse Project work along these same lines, using artistic practice to provoke social change by conducting socially-engaged (participatory) performance art works that merge artistic research with Chinese medicine – proposing a new methodology that ethically challenges current perception of what art and medicine can accomplish together in society. The ability of Qiscapes and Pulse Project to effect social change is enhanced by creating and utilising participatory research methods (63) to test, evidence and analyse the new understandings of art, medicine, the body and society that were co-created with participants within the performance encounter.

Currently, clinical medicine informed art has become more widespread – as evident in the recent series Inter-HER by Professor of Interactive Media Camille Baker, who has created empathic experiences for audiences using immersive installation and VR that address difficulties that women over fourty face with diagnosis and treatment of a variety of reproductive diseases – a project originally motivated by the artist’s own experiences (64).

There are also many institutionally supported art-medicine projects which differ from traditional art therapy that provide a series of ‘arts on prescription’ services, which generally refers to the social prescribing of artistic experiences as complementary treatment for biomedically diagnosed conditions. These services are widely available in the United Kingdom at institutions, such as the Devon Partnership NHS Trust (65), Arts and Minds Cambridge (66), Artlift in Gloucestershire (67), and initiatives such as the Performing Medicine (68), which provide training and wellbeing for healthcare professionals and students – as well as a wider focus on health, social justice and wellbeing for general audiences (69). There are also many similar programmes emerging globally in Australia, Europe, the United States, and so on.

The art-medicine projects mentioned above all share correspondences with Qiscapes and Pulse Project in their focus on using performance-led activities as prescriptions for promoting wellbeing and community building. The ‘arts on prescription’ series is more about using artistic activities (ranging from painting, to dance, theatre, music, and so on) to promote wellbeing – whereas the Qiscapes and Pulse Project use sound as a therapeutic strategy that uses co-resonance between the environment and the body to promote wellbeing. In a way that is more similar to Baker’s Inter/ HER (2023), the Qiscapes and Pulse Project use art to critically alter audience assumptions about medicine and the body, while providing immersive experiences that directly involve participants’ bodies and provoke critical thinking as part of the artistic reception process.

Nonetheless, Qiscapes and Pulse Project differ from Inter/HER and similar projects as they are focused on biomedical constructions of the body – and Qiscapes and Pulse Project are aimed at opening up discussion of the body and medical meaning making from a cross-cultural perspective that seeks to raise awareness of and explore East Asian medicine practices as a divergent position from which to understand and experience embodied wellbeing.

ART-CHINESE MEDICINE PROJECTS

Over the past twenty years, growing interest in using Chinese medicine as a source for artistic exploration and research has slowly but steadily developed. However, there is still limited discourse on this topic. Therefore, this section aims to provide a brief overview and analysis of Chinese medicine art projects, as this research area holds significant potential for further exploration, both for my own work and for other researchers.

Some recent projects have highlighted Chinese medicine’s emergence as a medium for socially-engaged artistic exploration. For instance, at the International Art Fair Survival Kit 8 in Latvia in September 2016, the festival focused on ‘social acupuncture’, viewing contemporary society as a body and using acupuncture as a metaphor for probing into society’s most critical issues (‘painful points’) (70), offering valuable social context for my exploration of Chinese medicine as a burgeoning creative tool for driving social change.

Similarly, artist Carissa Rodriguez’s photo series It’s Symptomatic/ What Would Edith Say? (2016) involved her acupuncturist diagnosing pictures of other artists’ tongues to raise questions about the connections between good health, good taste, bad health and bad taste within art production. While the artist’s intended meaning may vary, this project intriguingly utilises a Chinese medicine technique within artistic practice to explore concepts of the body and society, albeit indirectly. However, this project approaches Chinese medicine more as an appropriation (71), using its ideas to create an ‘exotic’ encounter rather than engaging deeply with the practice itself, its culture, or its unique characteristics.

One prominent example in this genre is Chen Zhen’s Crystal Landscape of Inner Body (2000), where the artist crafted twelve organs from blown glass. These delicate creations embody a fusion of Eastern and Western perspectives on the body in medicine, symbolising the inter-connections between the body, culture, and society. Chen Zhen’s own statement about the work reads:

“The particular geography of the body is called inner body landscape. According to Chinese it is meridians and channels of energy… Simply put, Chinese do not perform anatomical dissection. Crystal Landscape of Inner Body is made up of twelve clinical supervision beds that may be installed together or separately. Human organs, made of crystal, lay on the beds to form an “Inner Landscape” of the body… These organs are like spherical mirrors: by reflecting the positive and negative aspects of our environment, the “inner landscape” is transformed … A dozen entities that unveil the fragility of the body and the necessity of taking care of it.” (72)

Chen’s twelve glass zàng-fǔ organs find resonance with my own practice of sculpting bespoke soundscapes from participants’ 12 organ-networks during pulse analysis and point location performances. Moreover, both Chen’s glass sculptures and my sound compositions serve as objects that bridge art and science, as well as upholding diverse global cultures of embodiment. Together, they bring to life the otherwise imperceptible essence of the Chinese medicine concept of the body.

Similarly, artist Xiao Lu’s performance, titled ‘Tang Poem. Chinese Medicine. Copying. Time.’ (2011), explores the act of creating art as a means of cultivating and embodying health. These performances serve as a contemplation on medicine, aesthetic well-being, and on time itself. In Xiao’s performances, the past, embodied by a Tang Dynasty poem containing discussions on medicine, coexists with the present. This temporal transition unfolds as Xiao reproduces the ancient poem in the contemporary setting of the performance. Additionally, Chinese herbs take on roles as objects of both aesthetics and medicine within her artistic expression. Xiao provides further insight into this performance in the following passage:

“At the time I was taking Chinese medicine, and one day I copied out a Tang Dynasty poem using Chinese medicine for ink. It felt good, and I continued to copy out poems. My original plan was to spend a year copying out 360 Tang Dynasty poems, but after four months’ work, my condition slowly improved.” (73)

Chen and Xiao represent the visible forefront of a significantly larger, albeit relatively concealed (especially to non-Chinese researchers) community of artists. This community has actively employed Chinese medicine as a medium for cultivating aesthetic insights into the human body and our existence within the world, and their endeavours encompass a realm of knowledge practices that traverse the boundaries of time and space – between the present and past moments of poetic and medical meditation (such as those contained within poems of the Tang Dynasty era).

In 2018, during my tenure as an associate professor at the Roy Ascott Technoetic Arts Studio at the Shanghai Institute of Visual Arts, I had the opportunity to meet Yuk Hui (74).

Having previously engaged with his work The Question Concerning Technology (2016), I shared elements of my own research with him and it became evident to us that deeper exploration into the cosmotechnical dimensions of art, technology, and Chinese medicine could yield fascinating insights. As a result, we collaborated with renowned anthropologists of Chinese medicine, Professor Emerita Judith Farquhar and associate professor Lili Lai, to organise an interdisciplinary conference titled Art, Chinese Medicine, Technics (2019) at the University of Chicago Beijing Centre. This conference aimed to:

“…Conjoin these fields seldom considered together to explore new interconnections and hybrid practices. Yuk Hui delivered a keynote speech that sought to diversify the notion of technology and to identify differences in technical practice that might arise from closer attention to Asian theories both ancient and modern.” (75)

This gathering also featured notable participants such as Zhang Qicheng, a distinguished Chinese medicine physician, Wang Min’an, a philosopher of art, and a diverse array of artists, technicians, and scholars specialising in Chinese medicine.

BIOMUSIC AND SPATIAL SOUND:

SOUND MADE FOR AND FROM THE BODY

Here I briefly examine sonic performances that serve the purpose of either utilising spatial soundscapes to enhance the physical wellbeing of audiences, as seen in Rona Geffen’s The Sound is the Scenery (2017), or employing the human body itself as an instrument to produce spatial soundscapes, as demonstrated in the work of media performance artist Marco Donnarumma Music for Flesh II (2011-2012) and 0:Infinity (2015). These artists closely align with my own research, which focuses on using the body as a platform for soundscape creation and employing therapeutic spatial sound design to construct healing environments for bodily organs. Furthermore, Donnarumma, Geffen and I have collaborated with 4DSOUND to develop innovative spatial sound interfaces that engage with the human body in novel ways, as showcased in our performances at events like TodaysArt NL (2015) and TEDX Danubia Reflections from the Inner Mirror (2017). 4DSOUND’s aim in commissioning us was to investigate:

“…How spatial listening influences conscious states throughout the day and night. Together with a range of collaborators from the field of arts, technology and science, we investigate… how understanding these states can lead to new interactive forms of art. We explore new ways to physically connect the listeners with the surrounding space.” (76)

Known for his performance series Music for Flesh II, Donnarumma has developed an interface (77) that uses biomedical engineering and informatics to amplify a wide range of muscle ‘signals’ (mechanomyogram or MMG) not audible to the ‘naked ear’ (78). Donnarumma’s performances create streams of dramatically intense sounds – or ‘biomusic’ originating from amplifying the infrasonic signals of his body whilst it is in motion. See Fig. 13 below (79).

Figure 13: Music for Flesh II (2011-2012), performance with custom-built XTH Sense bioacoustic sensors, computer, loudspeakers and subwoofers © Marco Donnarumma. Photo: Marc Daniels.

For TodaysArt NL (2015), Donnarumma worked with the 4DSOUND team to develop 0:Infinity (2015), which is an immersive and interactive work that constructs an “unstable and reactive architecture of infrasound vibrations, audible sounds and high-powered lights” (80). Utilising ‘Xth Sense’ biotechnology, Donnarumma amplified participants’ infrasonic signals generated by blood flow, heart rate, and muscle contractions. Complementing this was Ubisense (81), a real-time location tracking software enabling live feedback on participants’ locations and interactions, thus shaping the evolving audio-visual landscape of 0:Infinity. This experience offers participants a distinctive, interactive, and immersive journey. Depending on their location and level of interaction, the visual and sonic structures transition from pitch-black silence to a breathtaking convergence of pulsating lights and intense bass vibrations that resonate throughout the venue. These ever-changing audiovisual forms reflect the unique interactions of each participant with light, sound, and data within Donnarumma and 4DSOUND’s system (see Fig, 14). As some participants recounted, this immersive encounter even led to hallucinatory sensations (82).

Figure 14: 0:Infinity at TodaysArt NL 2015. Circadian: 4DSOUND Electriciteitsfabriek, Den Haag © Marco Donnarumma. Photo: Georg Schroll. Image appears courtesy of 4DSOUND and Marco Donnarumma.

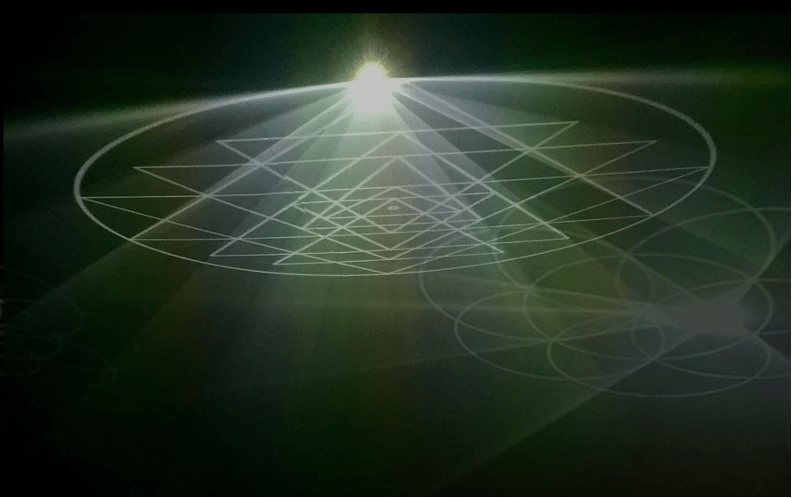

In The Sound is the Scenery (2017) (83), Geffen produced an interdisciplinary audiovisual performance that uses a set of tuning forks designed to resonate according to the frequencies of the orbits of specific planets (84). These planetary frequencies produced by the tuning forks at the same time are thought also to resonate with specific areas of our bodies – particularly the body’s seven chakras (85). Geffen took the creation of tuning fork ‘biofields’ for the body one step further than what one might see in sound healing communities to also consider the geometric patterns the sounds produce and how they align with sacred geometries found in nature, such as Fibonacci sequences (86). From this she created an immersive and transporting audiovisual experience.

By feeding an array of tuning fork frequencies into the multichannel 4DSOUND sound system, Geffen composed soundscapes that produced complex geometrical patterns which she designed in collaboration with mathematician Dr. Claire Glanois. To visualise the geometrical patterns that the tuning forks created, Geffen also collaborated with light designer Alessandra Leone. Together, they created interwoven, multicoloured sequences that mirrored the geometric patterns crafted by Geffen and Glanois. From the audience’s perspective, the gentle yet captivating tones of the tuning forks spiraled across the dimly lit expanse of the 4DSOUND system. Simultaneously, the illuminated pattern sequences were illuminated from above, enveloping the space with a ‘temple-like’ ambiance. Geffen’s primary objective in this performance series was to employ sacred geometry as a tool for healing. This healing process occurs by fostering a shared resonance between the audience’s bodies and the sonic patterns, along with the sacred frequencies of celestial bodies as shown in Fig. 15 -17 below.

Figure 15: The Sound is the Scenery, 2017. © Rona Geffen. Visuals by Alessandra Leone.

Figure 16: The Sound is the Scenery, 2017. © Rona Geffen. Visuals by Alessandra Leone.

Figure 17: The Sound is the Scenery, 2017, © Rona Geffen. Visuals by Alessandra Leone.

COMPARATIVE DISCUSSION:

0:INFINITY, THE SOUND IS THE SCENERY AND MY QISCAPES/ PULSE PROJECT

While Donnarumma’s 0:Infinity, Geffen’s The Sound is the Scenery and the Qiscapes/Pulse Project all share a common approach of employing audio design to create spatial sonic architectures that resonate with the audience’s bodies, they each diverge significantly in how they use sound to create meaning and in how spatial sound is designed in relation to the human body.

Donnarumma’s primary focus in 0:Infinity is on engendering a novel embodied perception of sonic architectures. It achieves this by integrating audience movement data within the performance space together with the internal bodily sounds that are captured via biosensors. This fusion generates a unique ‘third’ sound, exclusively audible within participants’ heads. However, 0:Infinity does not prioritise the promotion of audience health and well-being, which sets it apart from The Sound is the Scenery and Qiscapes/Pulse Project, where such aims are central.

Qiscapes/Pulse Project share correspondences with 0:Infinity in their utilising the body itself as a bio-musical instrument to produce live soundscapes – essentially using the internal body’s infrasonic patterns as a source for creating external bodies of digital sound that are spatially designed to co-resonate with audiences’ bodies. This approach contrasts with The Sound is the Scenery, which uses musical compositions based on geometric principles as the focus for sonic interaction with audiences’ bodies.

While 0:Infinity prioritises capturing human body interactions through Western mathematical abstraction and mechanical instrumentation, Qiscapes/Pulse Project and The Sound is the Scenery extend their objective to challenge the role of technology in society, by embracing a more ecological approach influenced by Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine. This approach fosters well-being by treating the body-environment relationship as an interconnected whole.

Lastly, what sets the Qiscapes/ Pulse Project apart is the utilisation of established clinical trials that have identified specific tones from traditional Chinese medical and music theory as beneficial to human organs. This approach results in therapeutic experiences that have already demonstrated to have a beneficial effect on human organs. It also presents a wider challenge to prevailing Western medical and technological paradigms, which often depend on mechanical instrumentation to privilege humans over nature, rather than fostering harmonious and beneficial relationships with the natural world… An inclination that tends to favor the technical over the biological, which may ultimately prove unsustainable.

In exploring biomusic, spatial sound, cosmotechnics, and the interplay of art and medicine, this section uncovers how Chinese medicine offers unique perspectives on medical interpretation, sound, and well-being. Its ecological approach to the body, spanning epochs from early civilisation to the present, provides a cosmological model for understanding and engaging with the body distinct from conventional biomedical paradigms. This discussion, along with Donnarumma’s and Geffen’s development of bio-sonic architectures, offers new perspectives on the body-environment relationship. Furthermore, by exploring both Eastern and Western dimensions of art and medicine studies, the projects discussed throughout this section provide further insights into how art and culture can diversify technological development, directing it toward enhanced human-environment wellbeing.

Through this review and discussion above, we come to understand how the projects Qiscapes/Pulse Project both contribute towards an alternative understanding of the intricate inter-relationships among the body, culture, and technology, as well as the cultivation of a transcultural imaginary of the body.

CONCLUSION

This article looked at a series of artistic interfaces that enable exploration of the human body from divergent perspectives through the fusion of sound, embodiment and medicine. In Qiscapes and Pulse Project, the Chinese medicine encounter is reimagined in digital performance contexts to forge cosmological ‘healing’ connections between individuals’ bodies, communities, and environments.

By embracing diverse medical paradigms, it becomes possible to gain a glimpse into the depths of the body’s mysteries and expand our understanding beyond conventional boundaries. We see the body emerge not as a standalone entity, but as an intricately interconnected and interactive system, continuously evolving and entangled with the surrounding lifeworld.

Qiscapes/Pulse Project and similar projects foster transdisciplinary approaches that bridge art, medicine, and technology, and invite collaboration among experts from various disciplines to uncover novel dimensions of the human body. This diverse integration challenges outdated paradigms and liberates us from modernist dualism, while allowing for a more multidimensional understanding of our being – in ways that defy temporal, spatial, and cultural boundaries. It encourages attentive rethinking and listening to our own bodies and those of others, which in turn cultivates solidarity. This profound connection fosters innovative practices and healing approaches centred around therapeutics (caring), reparation, and well-being.

As an emergent area of research development, Qiscapes and Pulse Project also initiate exploration of new artistic practices that communicate knowledge of Chinese and East Asian medicine practices to global audiences. By pioneering research in this emerging field, this article recognises the evolution of Chinese medicine and cosmotechnics as a crucial areas for future development. Its potential lies in its capacity to forge novel and non-modern connections among personal, historical, cultural, and disciplinary practices. This provides a diverse approach to standard art-science discourses, and in turn, enriches our understanding of the human body and opens new avenues for cross-cultural exchange.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

1. Iliana Fokianaki, “The Collective of Care: Responsibility, Pleasure, Cure, Part 2“, Berliner Festspiele (2022) <https://mediathek.berlinerfestspiele.de/en/gropius-bau/journal/the-collective-of-care-responsibility-pleasure-cure-2>, accessed November 2023.

BACK

2. Robert Storr, Writings on Art 2006-2021 (New York: Heni Publishing, 2021).

BACK

3. Volker Scheid, “Monk Yaodi and the Dao of Chinese Medicine“, Volkersheidnet (2022) <https://www.volkerscheid.net/post/monk-yaodi-and-the-dao-of-chinese-medicine>, accessed November 2023.

BACK

4. Patricia Leavy, Essentials of Transdisciplinary Research: Using Problem Centered Methodologies (Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, 2012) p. 30.

BACK

5. Gertrude H Hadorn, “Preface”, Unity of Knowledge in Transdisciplinary Research for Sustainable Development (Oxford: Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems/ UNESCO, 2009).

BACK

6. Henk Borgdorff, The Conflict of the Faculties: Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia (Leiden: Leiden University Press, 2012) p. 92.

BACK

7. See Borgdorff (2021) p. 93. [6.]

BACK

8. “‘Mode 1’ stands for a linear model of knowledge production, starting from within basic science [as] an independent and somehow protected area, followed by the field of applied science, in which knowledge is tested and used and to which actors from outside academia come to take up the knowledge and transform it by way of the industrial-economic complex into marketable products.” G H Hadorn, C Pohl and M Scheringer, “Methodology of Transdisciplinary Research“, in Unity of Knowledge/ Transdisciplinary Research for Sustainable Development (Oxford: Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems/ UNESCO, 2009) p. 25.

BACK

9. These sonic environments draw on clinical trials that use classical Chinese medical texts to test beneficial effects on specific organs using specific frequencies. This is discussed further in Section 3.2. See also [12.] ahead.

BACK

10. Here I want to emphasise that the words bio-signal and qi refer to matter-processes that. defy easy definition or semiotic confinement.

BACK

11. This project is still in an early stage of development and open to collaboration.

BACK

12. For surveys on Chinese classical literature and contemporary clinical practices involving the use of sound to heal the meridians and organs, see Hui Zhang and Han Lai, “Five Phases Music Therapy (FPMT) in Chinese Medicine: Fundamentals and Application“, Scientific Research 4, pp. 1–11 (2017) & Y-C Kim, D-M Jeong and M S Lee, “An Examination of the Relationship between Five Oriental Musical Tones and Corresponding Internal Organs and Meridians“, Acupuncture and Electrotherapeutic Research 29, Nos. 3–4 (2004) pp. 227–33.

BACK

13. I provide a very brief description of pulse diagnosis as a more comprehensive discussion is beyond the scope of this article.

BACK

14. This is expanded further in the ‘body ecologic’ discussion in Section 3.2., named “Introduction to Chinese Medicine Principles and the ‘Body Ecologic'”.

BACK

15. See Kim, Jeong and Lee (2004) pp. 227–33 & Zhang and Lai (2017) pp. 1–11. [12.]

BACK

16. Originally, I used SuperCollider (a language-based platform used for designing live audio environments) to translate each waveform I felt during my analysis of individuals’ pulses. However, during that time (2011–2015), the composing process in SuperCollider was extremely time consuming, as I needed to create libraries for sounds, inter-connect them, etc., and so I began seeking platforms that could more easily produce the types of sounds I required in live performance situations – which the 4DSOUND sound system was able to offer.

BACK

17. This spatial audio interface was created with 4DSOUND, using a bespoke touchscreen audio interface that connected with the 4DSOUND system. The 4D system is a 20m x 12m x 5m mobile structure that consists of twelve black columns, forty-eight high-density omnidirectional speakers, nine subwoofers and a black gridded floor. The combination creates a unique immersive sonic environment. The iPad audio interface contained five pages; each page included four effect knobs that were further divided into both yin and yang organs for each of the Five Elements. For example, the Spleen (yin) and Stomach (yang) – which are Earth elements – each had their own audio effects libraries within one page. These audio effects were programmed using specific frequencies (e.g., 440 Hz for the kidney-water system) and spatial sound sequence design – ‘expressions’ deemed appropriate for each organ-element. This was accomplished through intensive discussions with Paul Ooman, and by developing the interface via experimenting with the ways the effect knobs could produce pitches and spatial dynamics that best matched my own understanding of the tones and waveforms of peoples’ pulses in relation to the more abstract expression of the Five Elements/ wŭxíng (a concept discussed further in Section 3.2). To this end, the effect knobs allowed me to translate my pulse-reading notations by adjusting the sonic shape, volume and temporal dynamics of the 12 organ-networks within a live environment.

BACK

18. See Paul Oomen, “Listening to Space. The Innovative 4DSOUND System Allows You to Hear Music in Four Dimensions. Its Founder Explains How Some Artists Have Taken Advantage of Its Unique Set-Up“, Red Bull Music Academy (2016) <https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2016/11/listening-to-space>,

accessed November 2023.

BACK

19. See Kim, Jeong and Lee (2004) pp. 227-33 & Zhang and Han Lai (2017). [12.] See also [28.] ahead, which discusses the Huangdi Neijing.

BACK

20. See Donna Haraway “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective“, Feminist Studies 14, No. 33, pp. 575-599 (Feminist Studies Inc., 1988) & also Erin Manning, Relationscapes: Movement, Art, Philosophy (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2009), where the understanding of knowledge construction takes on ethical, embodied and relational dimensions as a critique of ‘objective’ knowledge construction paradigms.

BACK

21. Yuk Hui, the Question Concerning Technology in China: An Essay in Cosmotechnics (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2016) p. 10.

BACK

22. Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007) p.7.

BACK

23. See Stanford University’s description of biomedicine as a “global institution woven into Western culture and its power dynamics (…) The biomedical model is in fact so commonplace that it is easy to overlook how philosophically weighty (and contentious) its core commitments are: that health phenomena must be understood in terms of physical/ biochemical entities and processes, that experimental techniques are the preferred means of acquiring and assessing health-related knowledge, and that human bodies are best understood as composed of a collection of subsidiary parts and processes”. Sean Valles, “Philosophy of Biomedicine”, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2020) <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/biomedicine>,

accessed November 2023.

BACK

24. Healing, in this context and throughout this article, refers to a co-produced transformative aspect of knowledge production, i.e., knowledge produced between practitioner and querent, and, between two medical systems.

BACK

25. See Sarah Cant and Ursula Sharma, A New Medical Pluralism: Complementary Medicine, Doctors, Patients and the State (London: Routledge, 2004) pp. 13-14 for a discussion of how biomedicine as an institution subjugates medical practices outside the biomedical paradigm as ‘alternative’, thereby conferring upon them a marginal positionality. For a discussion of how the body is still assessed according to the logic of a ‘functional machine’ within the narratives of medical positivism, see Grant R. Gillet, Bioethics in the Clinic: Hippocratic Reflections (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004) pp. 45-47.

BACK

26. Ian Hacking, “The Disunities of Sciences”, in The Disunity of Science: Boundaries, Contexts and Power (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1996) p.44.

BACK

27. This is not only the case in the UK and other Western countries, but is actually a growing concern in China. See Jing-Bao Nie, Medical Ethics in China: A Transcultural Interpretation (London: Routledge, 2013) p. 182, for a discussion regarding concerns of how globalisation of Western hegemony is currently having a negative impact on traditional Chinese practices. For example, traditional Chinese medical ethics are losing – or may have already lost – their social significance altogether in China.

BACK

28. Some of the earliest records on clinical practice theories and strategies can be found in the Mǎwángduī and the Huángdì Nèijīng classic medical texts that date from the 2nd century BCE. The Huángdì Nèijīng or The Yellow Emperor’s Inner Canon Classic is a text dating back to approximately 320 BCE, but consensus differs on this date. See Gwei-Djen Lu and Joseph Needham, Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa (London: Routledge, 1980) p. xxix & Nathan Sivin, “Huang ti nei ching 黃帝內經“, in Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 1993) p.199 & Paul Unschuld, Huang Di nei jing su wen: Nature, Knowledge, Imagery in an Ancient Chinese Medical Text (Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2003) pp. 1-3. The Huángdì Nèijīng is referred to as the most significant text in the history of Chinese medicine. It was compiled over a five hundred year period by various anonymous authors and was later translated and formatted into various versions up until at least 725 CE (see Unschuld (2003) pp. 40-44). The book itself is divided into two parts, the Suwen and the Lingshu. The Suwen comprises nine volumes (chapters one to fifty-nine) and the Lingshu comprises the other nine volumes (chapters sixty to eighty-one). Together they make up eighty-one ‘difficult issues’ that refer to questions concerning the cultivation of health and the moral, spiritual, physical and environmental causes for disease. These questions are in the form of a dialogue between Huángdì (the Yellow Emperor) and his ministers or scholar-physicians. The main character is scholar physician Qíbó. The Suwen describes the medical philosophy of the inner and outer alchemical operations of yīnyáng, wŭxíng and the physiology of the zàng-fǔ organ-channel network. The Língshū describes particular pathologies in relation to acupuncture points and needling techniques (see Unschuld (2003) pp. 6-8).

BACK